A history of the Amiga, part 1: Genesis

Atari days

The generation of gamers who have been raised on Sony and Nintendo may not remember Atari, which today exists only as a logo and a brand used by a video game software company, but Atari essentially created the home video game industry as it stands today. The VCS was the first massively popular game console, and despite having incredibly primitive hardware inside, it managed to have a commercial life span far greater than any of its competitors. Much of this longevity was due to Jay Miner's brilliant design, which allowed third-party programmers to coax the underpowered machine to achieve things never dreamed of by its creators.

An example of this was Atari's Chess game. The original packaging for the VCS showed a screenshot of the machine playing chess, although its designers knew that there was no way it was powerful enough to do so. However, when someone sued Atari for misleading advertising, the programmers at Atari realized they had better try and program such a game. Clever programming made the impossible possible, something that would be seen many times on the Amiga later on in our story.

Having achieved such great success with the VCS game console, Jay's next assignment was designing Atari's first personal computer system. In 1978, personal computers had barely been invented, and the few companies that had developed them were often small, quirky organizations, barely moved out of their founder's garages. Apple (started by the aforementioned Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak) was one of the major players, as was Tandy Radio Shack and even Commodore (we will get to the full Commodore story in a future installment).

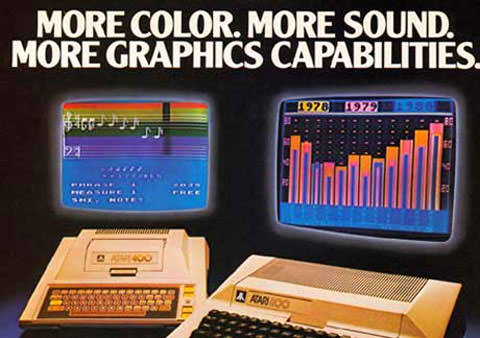

An early ad for the Atari 400/800. Note the years!

The computer Jay designed was released in 1979 as the Atari 400. A more powerful version, the 800, was also released with a better keyboard. At the time, most of its competitors were awkward, clunky machines, often large, heavy and temperamental, and if they created any graphics at all they were either in monochrome or, in the case of the Apple ][, limited to a palette of only eight colors. The Atari 400/800 machines had a maximum of 40 simultaneous colors, and featured custom chips to accelerate sound and graphics to the point that accurate conversions of popular arcade games became possible. Compared to an Apple ][ or a TRS-80, the Atari machine seemed to come from the future. The same thing would happen with the Amiga a few years later.

However, Atari management undermined the success of the 400/800 in several ways. Firstly, to avoid competition with the VCS, they downplayed the importance or even the existence of games for the platform, insisting that it be considered a "serious" machine. Ironically, when the company was struggling to produce a successor to the 2600, they ended up simply putting an Atari 400 in a smaller, keyboard-less case. Even worse, Atari was reticent about giving out information about how the hardware worked, thinking that such data was to be kept a trade secret, known only to internal Atari programmers. Some individuals, such as the superstar game programmer John Harris, considered this a challenge, and they managed to unlock most of the Atari's secrets by a process similar to reverse engineering. But the lack of strong third-party development for the computer doomed it to an also-ran status in the nascent industry.

After the 400 and 800 had shipped, Atari management wanted Jay to continue developing new computers. However, they insisted that he work with the same central processing unit, or CPU, that had powered the VCS and the 400/800 series. That chip, the 6502, was at the heart of many of the computers of the day. But Jay wanted to use a brand new chip that had come out of Motorola's labs, called the 68000.

The 68000

The 68000 was an engineer's dream: fast, years ahead of its time, and easy to program. But it was also expensive and required more memory chips to operate, and Atari management didn't think that expensive computers constituted a viable market. Anyone who had studied the history of electronics knew that in this industry, what was expensive now would gradually become cheaper over time, and Jay pleaded with his bosses to reconsider. They steadfastly refused.

The dream chip: Motorola's 68000.

Atari at this time was changing, and not necessarily for the better. The company's rapid growth had resulted in a cash flow crunch, and in response Nolan Bushnell had sold the company to Warner Communications in 1978. The early spirit of family and cooperation was rapidly vanishing. The new CEO, Ray Kassar, had come from a background in clothing manufacturing and had little knowledge of the electronics industry. He managed to alienate all of Atari's VCS programmers, refusing their demands for royalty payments on the games they designed (which were at the time selling in incredible numbers) and even referred to them at one point as "prima donna towel designers." His attitude led to a large number of Atari programmers quitting the company and forming their own startups, such as the very successful Activision, started by Larry Kaplan. Larry had been Atari's very first VCS programmer.

Jay had incredible visions of the kind of computer he could create around the 68000 chip, but Atari management simply wasn't interested, so finally he gave up in disgust and left the company in early 1982. He joined Zimast, a small electronics company that made chips for pacemakers. It seemed like his dream was dead.

However, as would happen many times in the short history of this industry, forces would align to make a previously impossible dream possible. While technology was advancing rapidly, the number of people who really understood the technology remained small. These people would not be limited by the short-sighted management of large companies. They would find each other, and together, they would find a way.

It was this feeling that caused Larry Kaplan to pick up the phone and make the fateful call to Jay Miner in the middle of 1982.

Larry was enjoying the fruits of his success with Activision, yet still felt the limitations of being primarily a developer for the Atari VCS. Video games were a hot property at this time, and there was no shortage of investment money that people were willing to put into new gaming startups. A consortium out of Texas, which included an oil baron (who had also made money from sales of pacemaker chips, which was how Jay knew him) and three dentists, had approached Larry about investing seven million dollars in a new video game company.

Larry immediately phoned Jay at Zimast to ask if he would like to be involved in this new venture. The idea was to spread the development around: Larry and Activision would develop the games, Jay and Zimast would design and build the new hardware to run them, and everybody would make money. They had to quickly decide on a name for the new venture, and "Hi-Toro" was chosen because it sounded both high-tech and Texan. The company needed a management person to oversee all this development, so David Morse was recruited from his position of vice president of marketing at Tonka Toys. A small office was located in Santa Clara, California, and the three co-founders got down to the business of designing the ultimate games machine.

It was around this time that Larry Kaplan began to get cold feet about the whole idea. Jay speculated that perhaps things weren't moving fast enough for him, or maybe he was worried that the games industry was becoming too crowded, but he suddenly decided to quit the company in late 1982. It turned out that Kaplan had been given a very generous offer from Nolan Bushnell to come back to Atari, an offer that later turned out to be less than expected.

In any case, Kaplan's departure presented the fledgling venture with a problem: they had no chief engineer. While Larry was a software developer and not a true hardware engineer, he had still been in charge of engineering management for the company. The next logical choice for this position was Jay Miner.

Jay knew this was his chance. He agreed to take over the position of chief of engineering at Hi-Toro under two conditions: He had to be able to make the new video game machine use the 68000 chip, and also make it work as a computer.

Tune in next week for Part 2: The birth of Amiga

User comments